The Real Impact of Automation: A Skills Revolution

Posted by Penn Foster on March 1, 2019

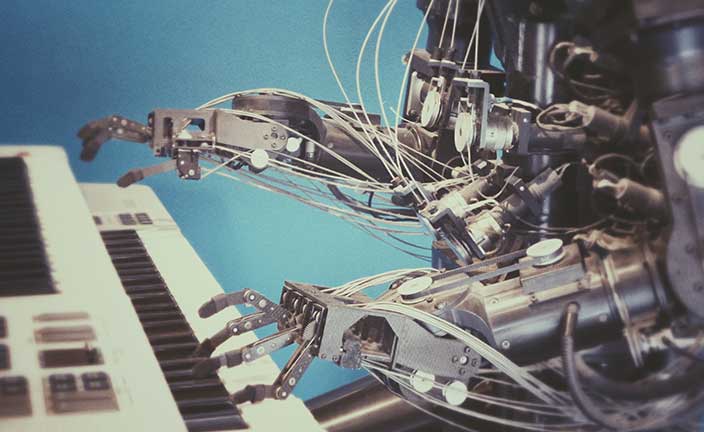

You've heard that the biggest enemies of the skilled worker in the last two decades have been automation and the constantly improving technologies that will make human work obsolete. If a machine can complete a task more efficiently at less cost, it makes sense to invest in cutting edge technology over upskilling workers. Conventional wisdom has us fearing a fully automated workforce because it means the eradication of middle-skilled jobs in almost every industry. Before completely investing in an automated future over developing workers' skills, consider this often overlooked, contrarian point of view: the impact of automation on the workforce will be incremental and, in fact, positive.

Jobs beyond the most basic routines are complex

The idea that automation in the workforce will eliminate full jobs is a misconception, generally not supported by facts. The McKinsey Global Institute, founded in 1990 as the research arm of McKinsey & Co. charged with developing a deeper understanding of the evolving global economy, says that less than 5% of jobs can currently be fully automated. 60% of jobs could be see an impact from automation, with 30% of their workflows effected.

While it can't be said that automation in the workforce will have no impact on jobs and industry, in the near term the majority of roles will remain, with smart, cognitive automation changing the way the work is executed. It is also worth noting that the common, fear-based narrative regarding automation ignores the positive change that happens with the growth and adaptation of new tech. These developments often spawn new industries, creating next-generation roles and opportunities.

Technological advancement doesn't always translate to increased productivity

Advancements in technology are often praised for increasing productivity in the workforce, but new tech doesn't necessarily translate to accelerated productivity. Automation in the last twenty year is instructive. According to author Oren Cass in his book "The Once and Future Worker," economy-wide productivity during 2000-2016 increased only 1.8% annually. As of 2016, productivity directly correlated to automation in work processes hasn't had a noteworthy increase since the 1980s.

One prominent study does report a negative relationship between robots and jobs, but the magnitude of its findings is interesting. Released in 2017 by the National Bureau of Economic Research, the paper was headlined in the New York Times as "Evidence That Robots Are Winning the Race for American Jobs" and in the Washington Post as "We're So Unprepared for the Robot Apocalypse." The actual effect identified by the report? A loss of 360,000-670,000 jobs over seventeen years, of which only half were in manufacturing. This amounts to a loss of only fifteen thousand manufacturing jobs per year, roughly 0.1 percent of average manufacturing employment during the period. At that rate, robots might, over a century, eliminate as many manufacturing jobs as were in fact lost during 2001.

The difference this time, and the cause of economic distress, isn't that productivity is rising; it's that output is not. From 1950 to 2000, while productivity in the manufacturing sector rose by 3.1 percent annually, value-added output grew by 3.6 percent " and employment increased, from 14 million to 17 million. During 2000-2016, productivity rose by a similar 3.3 percent annually. But output growth was only 1.1 percent " and employment fell, from 17 million to 12 million. Even with all the technological advancement of the twenty-first century, had manufacturers continued to grow their businesses at the same rate as in the prior century, they would have needed more workers " a total of 18 million, by 2016.

Change happens incrementally

Apocalyptic workforce prophecies of increasing job loss due to automation commonly ignore the gradual time it takes for change to occur and effect the real world. In the workplace, experts also often forget to take into account the time needed to retrain and upskill current employees. Instead, change typically comes incrementally, and shifts in practice usually move slower than expected.

Thomas Edison's development of the light bulb is a perfect example. Edison presented his invention, lit with power from his Pearl Street generating station, in 1882. What would eventually be a game changer for industry, however, took almost half a century to have impact. Forty years after Edison's initial presentation, less than 10 percent of the nation's 6 million farms had electricity.

Walmart took eighteen years to grow from $1 billion to $100 billion in U.S. sales. Amazon, likewise, hit the $1 billion mark in 1999 but took until 2017 to reach $100 billion across North America.

While digital product moves faster than physical, there are still certain constraints. Most recently, that can be seen in the self-driving car expectations that experts suggested would claim over 3 million driving jobs (among the largest job pools in the US). However, an article from the Wall Street Journal last week titled "Driverless Cars Tap the Brakes After Years of Hype" confirms that change, especially with technological advances, happens at a slower rates than projected.

We can prepare and adapt to advancements in automation through upskilling

While robot workers replacing humans will inevitably remain the workforce debate of the decade, we should also consider the more likely possibility of the opposite being true. Manpower Inc., a leading human capital management firm, released a recent study that shows more employers than ever - 87% - plan to increase or maintain headcount as a result of automation for the third consecutive year. Rather than reducing employment opportunities, organizations are investing in digital opportunities, shifting tasks to robots and creating jobs. At the same time, companies are scaling their upskilling so their human workforce can perform new and complementary roles to those done by machines. The "Skills Revolution" is in full flow and the impact of automation on job growth in their organizations is expected to be positive in the next two years.

Consider this: even with technological advances in automation making it possible for a machine to fully complete a task on its own in some cases, that machine was created by a human. Humans will need to be trained to monitor, repair, and complement the work done by the machines we rely on to make production and manufacturing easier. While some routine jobs will be outsourced to robots, there remain many more skilled positions that can't be easily filled. Investing in skills training and upskilling current employees can not only abate the economic fear of an automated workforce, but help employers prepare to stay on the cutting edge of industry and growth.